di Margarita Diaz

“By reading women writers, analyzing them, and attempting to make them better known across Italy, the collective could establish ‘an alternative genealogy of culture’”.

I planned my visit for the last Monday afternoon of my trip, promising myself that I wouldn’t leave Milan without stopping by. In her essay collection In the Margins, Elena Ferrante – one of my all-time favorite writers – had mentioned a women’s bookstore collective, the Libreria delle Donne di Milano, whose work had been a source of inspiration for her globally acclaimed Neapolitan Novels.

For that reason alone, it was on my “must-see” list.

Throughout the few weeks I had spent in Northern Italy, I’d leaned into my inner bibliophile, sauntering in and out of small bookshops, leafing through novels with crisp, aged pages, making mental notes of which writers I wanted to put on my reading lists – Lalla Romano, Anna Maria Ortese, Elsa Morante. Usually, booksellers would pay no mind. I’d linger awhile in a hallucinatory state, then say my pleasantries and go.

This shop felt different the minute I walked in. At once, I could feel myself inhaling old pages – that intoxicating book aroma – and the faint, lingering odor of cigarette smoke.

I had stepped into a delightfully analog space. Tall cherry wood shelves carried. I glanced at tables with green pamphlets and wooden racks of fading magazines displays of paperbacks, organized by topic, then author. There were political posters and bright-colored protest banners and art on the walls. Against a corner at the front of the space, a clothesline hung sheets of printed paper with various book recommendations.

It was immediately, painfully obvious that my presence was an interruption. All four women working inside the shop stared at me en masse. I didn’t know what to say.

I revel in speaking to strangers and asking questions, but my Italian had not progressed past the perfunctory. As I leafed through books, the group eyed me with curiosity. A woman seated in an open upstairs loft, tall and slender with light shoulder-length hair and a calm disposition, descended a narrow, spiral metal staircase.

She spoke English. “If you like, we have a pamphlet about the bookstore in English, so you can understand. I can show you.” Pointing to a stack of slim red leaflets, she asked why I came to visit the store. “We don’t get very many Americans,” she added.

“Do you want to come to our next meeting?” she then asked. A short, gray-haired woman walked up to us. The two quipped back and forth in rapid Italian – which I could only barely intuit was a discussion about me, about how I could possibly participate in a meeting if my Italian wasn’t good. Somewhere in the garble, I heard the gray-haired woman say emphatically, “Eh, lei è intelligente”.

Surprised, I beamed at the compliment.

Leaving the store with a small stack of books and pamphlets, I stopped to sit on a nearby bench to bask in the early September sunshine and wait for the tram, moved by what I had just experienced. I could already imagine my next visit, armed with better Italian to converse and engage. More than anything, I regretted that I wouldn’t have time to come to a meeting this time around – because, as impressive as the shop’s selection is, the bookstore isn’t entirely the point.

The Libreria delle Donne di Milano (The Milan Women’s Bookstore), on Via Pietro Calvi in the Zona Risorgimento, houses more than 7,500 carefully curated works, mostly in Italian, by 3,700 female writers from all around the world. Works by icons of Italian literature like Sibilla Aleramo, Grazia Deledda, and Elena Ferrante sit next to translated copies of works by anglophone writers like Virginia Woolf and Jane Austen. It is a refreshing, unapologetic, women-only space, where female voices are celebrated and encouraged.

Bookstores that sell only women writers are littered across Europe. There are several in Italy. But the Libreria delle Donne di Milano occupies a singular, unique place in the history of the Italian women’s movement.

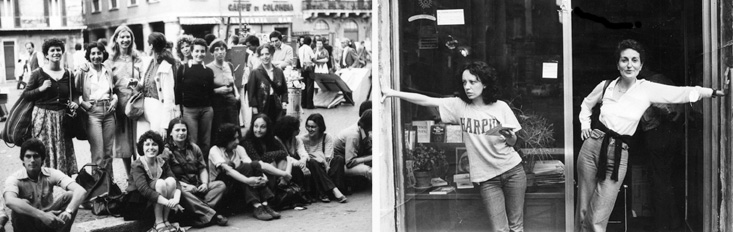

Founded in 1975, during the Anni di Piombo – a tumultuous decade in Italy’s history marked by strikes, protests, and political violence from both the far right and far left – the opening of the Libreria coincided with the birth of second wave feminist groups that were engaging in public activism across the country, becoming more vocal about issues like divorce and abortion.

At a time when women across the western world, particularly in the United States, practiced a feminism steeped in the language of equality – in which women needed to make themselves equal to men on a fundamentally unlevel playing field – the Italian feminists, and the founders of the Libreria delle Donne, had a different perspective. They believed that feminism must openly recognize that women experience the world differently – especially in a country like Italy, with its deeply ingrained paternalistic and patriarchal culture. They saw that the world they inhabited was built for and created by men – and that the creation of spaces separate from the traditional systems of male power, official party politics, the domestic sphere, and all that stood to limit a woman’s potential, was the true key to the emancipation they sought.

The founders, a collective of about a dozen women, came from all walks of life. They were lawyers and writers, artists, teachers, housewives. They craved a space in which they could use “the fire in their hearts and intellects to speak and write about their diversity, their desires, their passions.” In opening the store, they sought to build and preserve a tradition of women’s literature, predicated on the idea that those who move about the world as women do have a distinctive voice in their writing.

By reading women writers, analyzing them, and attempting to make them better known across Italy, the collective could establish “an alternative genealogy of culture,” placing writers like Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte, Ingeborg Bachmann and Anna Banti, at the forefront of a canon of literary tradition.

“It’s not that there weren’t any such books published in Italian, but either bookshops didn’t stock them or they were put away in corners; they didn’t have their own history, so to speak,” remembers Natalia Aspesi, a journalist and writer associated with the founding of the shop.

Milan was known as a capital of publishing for much of the 20th century, and the collective sought a place for themselves within that landscape. They encouraged members to share their thoughts, opinions, and expériences – starting a magazine, Via Dogana, and a publishing imprint to bring their ideas into the world.

One of their more well-known works, Non credere di avere dei diritti (which translates to Don’t Think You Have Any Rights), details the origins of the Italian women’s movement and offers a complex introduction to their theory of practice.

The book placed importance on group authorship, never attributing ideas solely to any one name within the impressive roster of intellectuals in the collective.

In tapping into a “new spirit of radical feminist publishing” that was emerging in the 1970s, the store also stocked and sold work from other feminist groups like the Rivolta Femminile, led by the activist Carla Lonzi, renowned for their iconic green pamphlets and manifestos.

Beyond the writing and the volumes sold, the collective wanted to translate words into action, viewing the shop as “a laboratory of political practice” and a community space. Like many other feminist collectives in Italy, they held the fundamental belief that shifts in societal and legal change for women began with establishing a safe space to discuss their experiences. They applied the term autocoscienza (“self-awareness”) to their method of consciousness-raising, rooted in dialogues in which women would discern personal experiences, find commonality, and ultimately attempt to tell each other’s stories.

In a sense, the practice of autocoscienza was part-group therapy, part-debate, part-collective philosophizing. At a time when political participation was not quite widespread among women, dialogues could serve as a helpful on-ramp for those interested in getting involved with the movement. When members of the collective came together to share their stories in small, intimate settings at the bookstore, they could become more fully aware of the ways in which their gender could constrict their freedoms. This, in turn, encouraged individual participation in more direct forms of action like demonstrations and protests, and autocoscienza became distinctive to Italian feminism at large, while the space of the Libreria and the ethos of the collective became entwined with the practice.

Today, given societal changes and a more widespread acceptance of feminism, there appears to be less of a need for the kind of consciousness-raising practiced in the 1970s. But as women’s rights across the globe remain under threat, perhaps a dedicated venue for discussion and philosophical debate, one with a history as rich as the Libreria delle Donne, remains necessary for the future of the movement. And there is no shortage of issues to consider: just last year, in the wake of last September’s national elections, thousands marched in the streets of Rome, Milan, and other cities, pressuring the government to uphold the 1978 law that guaranteed Italians access to abortion – a law that the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective actively supported.

“When this project was born, women had very few rights,” said one of the bookstore’s founding members in 2016. “It was a period of great conflicts, but over time things have changed. Today the position of women has changed. But it remains a place for meeting and discussion.”

Nearly 50 years since its founding, the bookstore still fosters discourse on topics ranging from maternity to bodily autonomy to feminist philosophy and dialectic – and continues to publish their Via Dogana magazine online. The bookstore collective – a group which takes turns every week volunteering and running the shop in half-shifts – remains its beating heart. And, attuned to the evolution of feminist thought, each shelf reflects the tradition and genealogy of women’s literature that they continue to build.

(italysegreta.com, settembre 2023)